Renzo’s Story

Written by Simon Bidwell for his new blog Andean Observer, this is the story of Eleven-year old Renzo, who left his parents home in Lima’s San Juan de Miraflores district to live with family in Arequipa.

On the sixteen-hour journey to Arequipa, he was sleepless, panicky and intermittently nauseous.

Over the next few days Renzo suffered from severe separation anxiety. He cried quietly in the room he had to share with Gerardo, and when a call was put through to his parents, sobbed down the phone to his mother.

Lizbeth was less than empathetic. “Aunt!” she shouted down the phone, in front of her nephew. “He’s been blubbering all day! He misses your teats!” I told her I was taken aback by such vulgarity, and she chortled.

When he forgot his homesickness, Renzo brought out a series of anecdotes of life in the barrio of San Juan de Miraflores. This is one of the “old new” areas of Lima; once a pueblo joven, it gradually built itself up into working class respectability – though is now plagued by the crime and insecurity that spares few parts of Peru’s teeming capital.

This time it was Lizbeth who was a bit shocked, as she listened to the tales. “That area’s gone downhill”, she said, shaking her head. “When I used to stay there as a student, it was tranquilo”.

With casual relish, Renzo told us of how he had been attacked in the park where he liked to play football. “One time I was in the park with my bike, and these guys came up and robbed me at gunpoint. I resisted, and tried to get away on my bike, but they ran after me and threw me to the ground. They stole my helmet and left me there”.

How old were these guys, I wanted to know. About seventeen, thought Renzo. And they

had pulled a gun on him for his cycle helmet? “It was a motorbike helmet”, he said, as if that explained everything.

Renzo shrugged that off plegmatically as an isolated incident and said it didn’t worry him to go back to the park. “I’m not afraid of anything”, he claimed. But playing and wandering on the streets, he’d been witness to at least two other violent crimes.

One time he’d seen a young guy with his girlfriend get attacked by four muggers, who stabbed the young guy in the leg before running off with his possessions. “Blood came spurting out”, according to Renzo.

The people of the neighbourhood came out en masse, but the muggers were long gone. The kid was taken to hospital, where a piece of the knife was removed from his thigh.

Another time Renzo saw a man get grabbed by two guys who ordered him to “give us all your money”. When the robbery produced little yield, they got angry, shouted “fuck, why don’t you have any money?”, and hit him in the head with a tyre iron.

Renzo also claimed to have witnessed a gunfight, just a couple of blocks up from his house.

“The U and the Alianza (Alianza Lima and Universitario de Deportes, rival groups of football hooligans) were fighting, and the police came and started to fire in the air. Then everyone started to shoot at each other”, he recounted.

Renzo said he watched from a roof, about 6 or 7 metres away through a peephole in a steel wall. Had anyone been hit in the gunfight? “Sure, lots of them were hit – in the leg, in the arm, the chest, the stomach, the face”.

Two of the Alianza cohort were killed, said Renzo. The police were greatly outnumbered and retired from the scene. “Later the Alianza went to look for the guys from the U, and killed seven of them. They cut their throats with big knives”.

It was hard to know how much of this to believe, as when I pressed for details of the incidents in question they were supplied in exaggerated, improbable, and somewhat inconsistent fashion.

But Renzo’s world was was starting to sound uncomfortably like City of God.

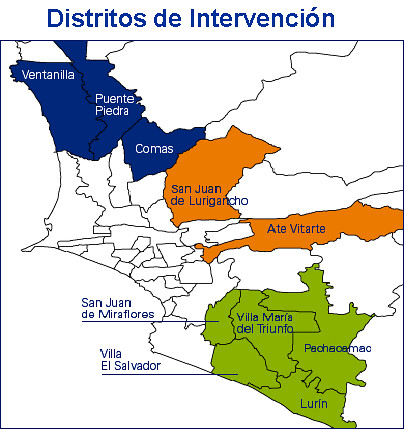

He was fascinated with the street gangs that wandered through his barrio from even rougher areas like Villa El Salvador and San Juan de Lurigancho, home of Lima’s notorious penal facility.

Like a budding social worker, Renzo deconstructed their criminality. “They’re people who haven’t had any education, their parents have treated them bad, that’s why they’re like that. It’s not their fault; it’s the fault of the parents”.

So he wasn’t afraid of the gangs, I asked a little incredulously. He shook his head.

“They don’t do anything to us kids, they just fight amongst themselves. They steal the arms to defend themselves against the other gangs, or the police. Sometimes the commit a crime so they can get taken to jail, then they escape and steal weapons off the police”.

So when the gangs were around, was he happy to just play football in the normal places?

Renzo paused. “Well, when they’re around, I don’t play. I want to watch them”. He ruminated a second. “It’s ok for me. But I do worry about when my parents go out. I worry that it’s not safe for them. I can take a risk, but I don’t want them to. I say ‘no mamá, don’t go out on the street'”

For all the bravado, I wondered if Renzo wouldn’t prefer to live somewhere that didn’t feature acts of mortal violence as part of life’s daily tapestry. He’d grumped that in suburban Arequipa “there’s no kids; there’s no football on the street”, but I asked him

if he wouldn’t like to be somewhere safer.

He shrugged. “I’d live wherever my parents were”.

“Ok, so assuming your parents were with you, where would you prefer to live?”, I queried.

“If my parents were in Lima, I’d prefer to live in Lima”, he affirmed. “If my parents were in Arequipa, I’d live in Arequipa”.

Tags: arequipa, crime, lima, san juan de lurigancho, san juan de miraflores, villa el salvador

![Peru’s Plans for Global (Foodie) Conquest [Featured]](http://farm4.static.flickr.com/3248/2894184868_5127efeb94_m.jpg)