The revolt of Túpac Amaru II

Born José Gabriel Condorcanqui in 1742, he was the great-grandson of the last Inca emperor Túpac Amaru. Like his great-grandfather before him, he was destined to resist the Spanish occupation, and, like his great-grandfather before him, was destined to meet the same fate.

Peru in the late 1700s was not a pleasant place. The Spanish had ruled for 200 years, during which time the indigenous population had been forced into slavery. The encomienda system ensured that Spaniards ruled over parcels of indigenous land and that the people living on that land were considered nothing more than beasts of burden.

Túpac Amaru II

When this system was abolished shortly before Túpac Amaru II’s birth, and “the Indians” were promoted in status to human being, little changed. Natives continued their forced labour through economic slavery. Taxes were levied on these “free” people which they could only pay by toiling in the fields for their masters, or by being worked to death in mines, or in work houses producing textiles. Taxes in the way of 100% or more kept the natives indebted and their masters wealthy.

The Catholic Church, successful in forcing the natives into the foreign religion of Jesus Christ with threats of torture and death, also grew rich from exploiting the indigenous. In addition to forcing natives to work on “public projects”, they conducted forced collections for saints days, and collections for attending church. The natives paid this extra religious tax for fear of being accused of being unchristian or fear of an eternity of riving agony in the fires of hell – a possibility they had been convinced was real.

Early life

José Gabriel was born in Tinta in Cuzco. He was a “mestizo” mixed race, with Spanish blood and the wealth and opportunities that that entailed. On his mother’s side, he was a direct descendent of Túpac Amaru, leader of the final failed stage of Inca resistance who in turn was son of Manco Inca, son of Huayna Cápac and half brother to Atahualpa and Huáscar.

José Gabriel received an education at the Jesuit church of San Francisco de Borja and went on to be granted titles by the Spanish vice royalty. He married and Afro-Indigenous woman in 1760 before inheriting authority over Tungasuca and Pampamarca from his older brother. He was of course, answerable to the Spanish governor.

Identifying significantly with his indigenous heritage, José Gabriel was not blind to the suffering of his people. He repeated lobbied for better treatment of the indigenous from his position of relative power. What wealth he had it is said he used to alleviate the suffering of natives in economic slavery.

Angered that his calls for humane treatment were at best ignored and at worst ridiculed, he grew increasingly embittered.

He read the famous Royal Commentaries book by mixed-race indigenous author Garcilaso de la Vega, who almost 200 years earlier wrote an account of the history of the Incas that portrayed their culture in a positive light. The Spanish had since banned the book for fear that it might lead to a revolt.

Revolt

His hatred for his oppressors grew ever stronger and he decided to organise a rebellion.

He began by refusing to carry out his responsibilities of debt collection on the indigenous under his authority. He was immediately threatened with death by the Spanish governor he answered to, Antonio de Arriaga.

Not on best of terms with the governor, he still attended a banquet with him that was hosted by a priest they both knew. Arriaga left later that night and was drunk. José Gabriel followed him outside where several of his supporters were waiting. The kidnapped him and spirited him away to a secure location where he was forced to write letters to tens of Spaniards arranging a gathering. They fell for the rouse and were surrounded by José Gabriel and 4000 indigenous rebels.

José Gabriel then publicly declared he was changing his name: he was now Túpac Amaru II, leader of a renewed indigenous resistance.

The Spaniards were executed, starting with the governor José Gabriel.

2000 more natives joined the ranks of Túpac Amaru II’s rebels and they marched towards Cuzco. As they did so, they gained control over several provinces around the city. In the towns of these provinces, where Spaniards ruled, the natives raided Spanish property and after decades of oppression killed every Spaniard they saw.

To put down the rebellion, in 1780 Colonial Cuzco sent out 1,300 soldiers. These were made up of 578 Hispanics and 722 indigenous loyalists. The two forces met in Sangarara when the rebels won a decisive victory and seized the weapons and supplies of their enemies.

Without orders from Túpac Amaru II authorising them to do so, his indigenous rebels viciously slaughtered all 578 Spanish soldiers. This ended all potential support by Spanish-descended Peruvian-born Creoles and removed any idea of independence from Spain in their minds. They rallied behind the Spanish vice-royalty.

From then on, the rebels suffered a number of defeats, and Cuzco was reinforced by troops sent from Lima.

Languishing in the countryside with no way to capture the imperial capital of his forefathers, the Spanish had time to convince two of his officers to betray him. Túpac Amaru II was captured and his rebels defeated. He was taken to Cuzco’s Plaza de Armas to be executed.

Cruel execution

Painful death

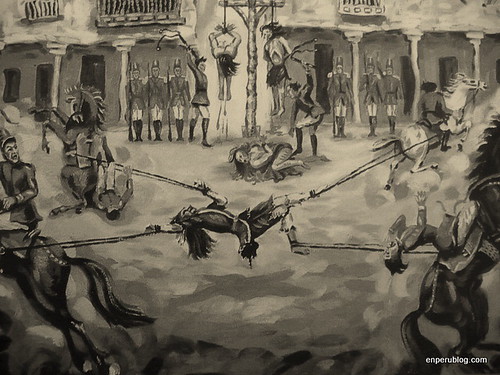

Proficient in their barbarity, the Spanish forced Túpac Amaru II to watch the execution of his wife, eldest son and brother-in-law. They were hung in public, along with many of his friends. Unfortunately, his wife’s neck was too thin to be chocked to death by the thick rope. So after being cut down and thrown to the ground, she was kicked to death.

His execution was to be worse.

He was subjected to agonising torture before having his tongue cut out. Already in excruciating pain, his arms and legs were tied to four horses which then galloped away in opposite directions. To the disappointment of the Spanish rulers, his limbs were not ripped from his body in a violent and bloody display. So finally he was killed by decapitation.

Aquí no hay sino dos culpables: tú por oprimir a mi pueblo, y yo por querer liberarlo

Here there are but two who are guilty: you for oppressing my people, and I for wanting to liberate them

Natives in the surrounding area continued to revolt, so the Spanish rounded up the remainder of his family and killed them all. Only his 12 year old son was spared a violent death, at the last moment he was instead sent to Spain to die after a life in prison.

Gruesomely, Túpac Amaru II’s body parts were strewn across the areas loyal to him as a warning to the natives. His properties and those of his supporters were burned down, his lands salted and distant relatives relieved of all rights, privileges and possessions.

Oppression

Photo by Martin Chambi

Soon after, in 1781, the Spanish colonisers introduced strict new laws. All indigenous customs, traditions, culture, language, song and free expression were outlawed. Indigenous Peruvians were forced to wear the peasant costumes that are still seen today, and wearing anything else would mean death. Speaking native languages was equally illegal. Considering yourself to be “Inca” or of any other group was illegal. Dances and songs were illegal. People were forced into churches and to abandon anything considered pagan.

To this very day, poor Andean people adhere to the Spanish-enforced dress code. Even the colourful dress of the Quechua people around Cusco is Spanish. Beneath the red ponchos of the men are Spanish peasant clothes, and the woman wear what are nothing more that European dresses with indigenous patterns and of local materials.

To this very day, poor Andean people are ashamed of speaking their native languages. Asking an indigenous person if they know Quechua, for example, might get a shy and tepid “yes”. In the cities, populated by mixed race Peruvians, being from the mountains and being indigenous is downright shameful. That you or your parents speak Quechua or Aymara is a source of ridicule. It makes you a serrano, a cholo, an unclean uncultured immigrant.

Proud (Martin Chambi)

Clear vestiges of this barbaric Spanish law existing today in 21st century Peruvian culture.

In Andean schools, the loss of thousands of years of heritage continues as indigenous languages, customs and dance are considered a waste of time and are not taught. Huge regions of the Andes have populations who don’t know a word of their native language, or identify with their culture.

Since the times of plenty, the times before the Spanish arrived, they have been denied education and nutrition. A healthy and highly skilled intelligent people have been transformed into people who are malnourished, don’t know the benefits of eating vegetables and haven’t been taught personal hygiene or disease prevention. Along with the loss of cultural heritage and history, they have lost all the knowledge of their ancestors – great monument builders, engineers, biologists, astronomers, knowers of the natural world around us.

The feelings of indigenous shame are now so woven into the fabric of modern culture that they may be difficult to change, and the newfound and fashionable “pride” of Peruvian culture by the urban classes doesn’t seem to extend to daily life or beyond an image to project for commercial exploitation.

Tags: aymara, catholics, colonial, cusco, customs, incas, independence, indigenous, jesuits, manco inca, poverty, quechua, rebellion, slavery, spaniards, tupac amaru, tupac amaru II

![Little town of Quince Mil is becoming a Hotspot [Featured]](http://farm4.static.flickr.com/3287/2690200819_25e3265f5f_m.jpg)