Colonial-era buildings in the historic center of Cusco risk collapse

By Roxabel Ramón for El Comercio

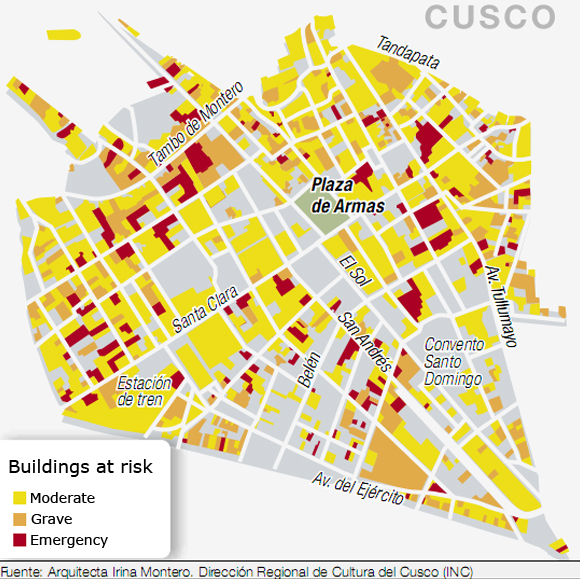

It is a problem that has been growing slowly for some time, but has been accelerated by the heavy rains that afflicted Cusco earlier this year. Despite the historic centre of Cusco being a UNESCO World Heritage site, it’s a problem that doesn’t seem to worry local authorities one bit.

Sad decay

You only need to walk a few metres out of the Plaza de Armas to find the adobe walls of colonial-era buildings bulging out or hanging at angles that can only be maintained by large numbers of huge trunks of wood propped up against them. Four main streets have even been closed to vehicles for the immanent risk the walls pose and the space taken up by the beams. According to the National Institute of Culture (INC), it could only take the vibrations from one small vehicle to bring down the walls that once resisted earthquakes.

The heavy rains have recently accelerated the process of decay. As many as 52 additional buildings are now at risk and seven walls have already collapsed, killing two people.

“The only thing we can do is take emergency action and place wall supports”, explained Irina Montero, head of the Commission for the Implementation of the Master Plan for Cusco, part of the INC.

This “plan”, which has existed since 2005, is a joint project between the INC and local authorities, it’s purpose to prevent further deterioration of properties and to provide a framework to allow authorities to expropriate historic buildings that have been abandoned.

Five years have passed since the initiative began and the special unit the plan was supposed to form to carry out the various processes has yet to be created because of conflicts of ideas between the local authorities and the INC.

“The INC doesn’t let us work”, complains the mayor of Cusco, Luis Flórez.

“The local authorities are only interested in political benefits”, responds the INC.

Both are currently working independently carrying out the same work of cataloguing buildings, duplicating effort and expense.

Moreover, neither is able to invest one penny in those buildings which are privately owned, i.e. the majority of them, because of strict laws that control government spending.

“The problem is that almost all those who inhabit these historic buildings are people of low income, which begins a vicious cycle”, states Irina Montero. For the INC to authorise the restoration of the homes, the owners must pay for an expensive technical evaluation and then buy the specialist materials themselves. The problem is, the cost of doing so is equivalent to the cost of purchasing up to three new houses in another part of the city.

This is the case, for example, for a colonial home on the forth block of Meloq street, where 18 families live among walls that are falling apart.

“We’ve grown accustomed to living in a state of fear. The INC doesn’t let us repair a thing, but nor do they offer alternatives”, complains Andrea Cáceres, one of the inhabitants.

Local authorities of Cusco have recently introduced one possible alternative: sponsored loans from local institutions and international funds so that locals might undertake the restoration process.

But some state that this idea put forward by the mayor is a non-starter. Just 10% of residents have actual ownership of their properties or any form of official documentation – the most basic of requirements to be granted any form of loan, and itself an expensive process to undertake.

UNESCO recently requested a report on the current situation on the historic centre of Cusco. There’s a serious fear that they’ll include Cusco on their at-risk list, though some point out that this would be beneficial as it would force incompetent authorities to finally take action. This is a view shared by architect Marcel Rodríguez, who estimates that any earthquake above 6 on the Richter scale would wipe out all the structures in Cusco rated as “emergency cases”.

Tags: adobe, colonial, cusco, flooding, historic buildings, INC, unesco