The Peruvian “Desert”

I mentioned the giant sand dunes north of the city of Lima, and it was commented how fascinated foreigners are with Peru’s desert coast, but is it a desert at all? Here is someone else’s experience…

My companions and I had been driving south down the stunning desert coast of Peru for nearly a day before we begin to wonder what the locals call this parched stretch of land that skirts the Pacific. We’ve all heard of the Atacama Desert in Chile, and the dry basins of Patagonia in Argentina, but none of us knew Peru was home to impressively huge sand dunes and sprawling, rocky wastelands. Curious, I inquire at a gas station south of Chiclayo.

“What is the name of this desert?” I ask the attendant as he wipes down my wind shield.

“This,” he says, happily gesturing at the barren expanse all around us, “is not a desert.”

I look sceptically out at the dry landscape. “What do you mean? Does it rain here often?”

The attendant grins. “It almost never rains here. It is like a desert.”

“But you just said this isn’t a desert.”

“That’s right,” he says. “This is not a desert.”

Perplexed, I pose the same question to a handful of Peruvians in the gas station snack shop, and they all tell me the same thing: This dry and dusty coastal strip of Peru – even with its jagged moonscape and curving sand dunes – is not a desert. It is something else. Something that, for whatever reason, does not have a name.

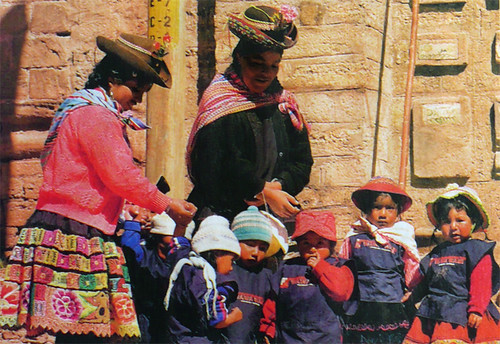

Few visitors to Peru know of this coastal desert, and fewer still make any effort to see it. Rather, travellers visit Peru for its legendary Andean peaks, lush Amazonian jungles, ancient Inca ruins and lake-studded highlands – and it is certainly no different.

Completely contrary to expectations, however, this road passes through sudden stretches of the most gorgeous desert I’ve seen since I travelled the Mongolian Gobi and the Egyptian Sahara. Oddly, unlike the Gobi or the Sahara, this desert had no reputation and (as far as I can tell) no name.

As we make progress into Peru, however, the coastal geography begins to make sudden changes. Just as I’m getting used to the sweeping desert surroundings, I will crest a ridge and drop down into a blindingly green river valley, studded with villages and sown with lush, irrigated fields of sugar cane, cotton and alfalfa. Then, just over another ridge, I’ll drop back down into a lifeless desert.

It takes a flurry of map research before I’m able to figure out what I’m seeing: Though this Peruvian coast receives little annual moisture beyond a dirty winter fog, more than 40 rivers roar out of the Andean highlands with enough force to cross the desert and reach the sea. Each of these river valleys creates its own riparian oasis, and – thanks to the rich highland silt contained in the waters – agriculture thrives here, supporting towns and cities all along the Peruvian coast. Unlike most rainless areas of the world, the Peruvian desert is home to a large population, including four of the nation’s five largest cities.

Travelling further south along the coast I finally get my desert epiphany from a matronly desk clerk at Nazca’s Alegria Hotel. “The coast of Peru is a dry place,” she tells me with a shrug. “But it’s too normal here to be a desert. I think it must be something else.”

The more I consider the woman’s dismissive logic, the more it makes sense. Deserts are supposed to be foreboding places, suitable only for mystics, nomads and wavering apparitions. For Marco Polo, the emptiness of the Gobi was filled by goblins; Pliny’s Sahara was haunted by phantoms. The coastal desert of Peru, on the other hand, is populated by oases full of workaday Peruvians – and it more or less has been this way for the past 6,000 years.

Perhaps, then, deserts are as much a matter of psychology as science. Regardless of the evaporation-condensation ratio along the Peruvian coast, the desert here has remained nameless because there’s too much human company to be had. What’s a desert, after all, if it isn’t deserted?