The Chuño – Dehydrated Potato of the Andes

The Chuño (or tunta) has fed families in Peru’s altiplano for more than seven thousand years. Today, with the growth in popularity of Novoandina food, the humble chuño has been thrust to the forefront of Peru’s gastronomic scene.

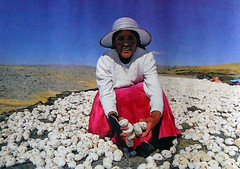

3,800 metres above sea level, the locals of the district of Ilave, in the province of Collao in Puno, produce a dried potato they call the tunta. Details of its preparation have been passed down from generation to generation, feeding the population of Peru’s high altiplano for thousands of years.

* * *

Process

It takes about 50 days to make good quality Chuño, the process goes something like this…

It takes about 50 days to make good quality Chuño, the process goes something like this…

Gather the potatoes to be worked with. Tonnes of Locka, Sani Imilla, Chaska and Occocuri potatoes are brought from growing regions like Andahuaylas and Arequipa where there is a more stable climate.

Sort the potatoes, divide them by their varieties and weight, removing those that have gone bad.

Those potatoes that have passed the selection are left overnight, for three or four nights, in the open fields of the altiplano, where during the winter the temperature drops far below zero and they are frozen. In the mornings they are collected and protected from the warm sun.

“If the strong rays of the sun fall on the potatoes they go purple of black, from these you can only make Black Chuño, not the White Chuño or tunta“, explains Andrés Muñeico, a tunta producer from the rural Chijichaya community.

If the potatoes sound like rocks when hit together, it is time for the next phase. They are submerged in a river in mesh cages for up to thirty days where they are slowly cleaned.

If the potatoes sound like rocks when hit together, it is time for the next phase. They are submerged in a river in mesh cages for up to thirty days where they are slowly cleaned.

When removed from the river, they are placed for one final night in the open to be frozen again.

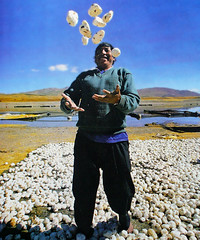

The next day they are pealed and washed once more. To do this, the potatoes are placed in a net at the shores of a river. In rubber boots, the townspeople stomp on the rock hard potatoes which, pushed together inside the net, rub against each other and peal themselves.

Left to dry for another week among the Andean grass called ichu, they end up an intense brilliant white colour.

* * *

The number of dishes you can make using tunta is surprising – Andean mothers demonstrate a lot of culinary creativity when feeding their families, as shown at the “First Gastronomic Competition with a Tunta Base”, organised by the Ministry of Agriculture. Cooks from twelve community restaurants, known as comedores populares, fought to win the top prize and entered a variety of dishes including Escabeche de Tunta, Ocopa de Tunta, Tunta Rellena (Stuffed Tunta) with Charqui (beef jerky) and cheese, and a tunta stew.

The number of dishes you can make using tunta is surprising – Andean mothers demonstrate a lot of culinary creativity when feeding their families, as shown at the “First Gastronomic Competition with a Tunta Base”, organised by the Ministry of Agriculture. Cooks from twelve community restaurants, known as comedores populares, fought to win the top prize and entered a variety of dishes including Escabeche de Tunta, Ocopa de Tunta, Tunta Rellena (Stuffed Tunta) with Charqui (beef jerky) and cheese, and a tunta stew.

Rodolfo Tafur, a scholar of Andean gastronomy, is convinced that the tunta can help push the cuisine of the altiplano to national and international success. “Aymara cuisine is a movement that is ever more fashionable, there is a big market for the people of Puno to satisfy”, says Tafur. He goes on to explain that the chuño or tunta could even improve establish dishes from Lima – a city declared the gastronomic capital of the Americas.

Jorge Clave, the director of Puno’s first school of gastronomy called Egatur agrees. “We are making our students work with ingredients from the region, taking advantage of what we have on hand, which as we’ll show, are really very good”.

The Tunta Sour, a variation of Peru’s famous national drink, was one of the many menu items created by Clave’s students, and is a drink with which everyone who is working hard on promoting the tunta can toast with pride.

Translated from El Comercio.

Tags: andean food, aymara, chuño, food, novoandina, potatoes, puno, tunta