Caravelí

At 12 hours from the Peruvian capital Lima, Caravelí, in the Arequipan province of the same name, was lucky to survive and keep – thanks to its relative isolation – its splendid bodegas of wines and piscos. Other towns in the south weren’t so lucky and were pillaged and burnt to the ground by Chilean troops in the War of the Pacific. This year the town presented itself in the national pisco contest that took place in Lima and took first place for its exemplary pisco of black creole grape, called El Comendador.

Written by Álvaro Rocha Revilla

Caravelí feels disconnected to the rest of the world. And in a certain sense this is true. In the almost two hours it took to get up here from the coast, from the turn off at Atico, we haven’t crossed paths with a single house, tree, river… nothing. Stopping on a curve on this abandoned road to nowhere, there below we saw a small green smear floating on a vast barren desert. Not just any desert – its dunes of sand and its rocky expanses have tones of red and salmon. However in this very dry land, apparently completely infertile, is produced one of the best piscos of Peru.

If were turn our heads, just a little, away from the spectacular desert scenery, to the left we see the Sara Sara mountain. Here in 1996, thanks to global warming and the melting of its ice caps, the mountain revealed, in perfect condition, a preserved mummy from pre-Columbian times. Called Sarita, the mummy is now exhibited in the Museo de la Universidad de Santa María in Arequipa. We also see the peak of Solimana and the Coropuna, the later being the highest volcano in Peru at 6425m.a.s.l.

It’s surroundings, the barren desert, volcanic peaks and the flamenco-filled Parinacochas lagoon below Sara Sara give the forgotten town of Caravelí a special atmosphere.

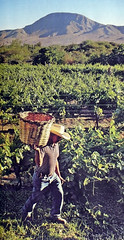

Vineyards

Caravelí was the first part of Peru to be divided up and given out to Spanish conquerors. On the 3rd of July in 1532, Francisco Pizarro authorised the issuing of Caravelí to Cristóbal de Burgos. The introduction of the first grape plants didn’t take long. Evidence shows the first was planted in 1548 in the grounds of Álvarez de Carmona for the Jesuit monks. From then until the time of Peruvian independence – when the town was used by patriot Mariscal Miller as a base to hunt down royalist Ameller – the town survived commercially as an exporter of grape produce. When the town was levelled in republican times by an earthquake in 1868, the town’s industry provided it with the ability to slowly recover.

Caravelí was the first part of Peru to be divided up and given out to Spanish conquerors. On the 3rd of July in 1532, Francisco Pizarro authorised the issuing of Caravelí to Cristóbal de Burgos. The introduction of the first grape plants didn’t take long. Evidence shows the first was planted in 1548 in the grounds of Álvarez de Carmona for the Jesuit monks. From then until the time of Peruvian independence – when the town was used by patriot Mariscal Miller as a base to hunt down royalist Ameller – the town survived commercially as an exporter of grape produce. When the town was levelled in republican times by an earthquake in 1868, the town’s industry provided it with the ability to slowly recover.

Bullet holes

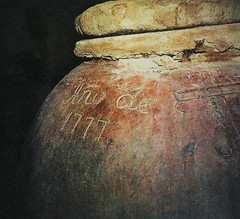

“Abundant tinajas (clay pots for fermentation), with bullet holes, are a testimony to the barbarisms lived during the war with Chile. Among the geopolitical objectives of Chile was to end the wine and pisco industry in Peru to aid the start their own, and to this end their armies destroyed machinery and shot at fermentation jars”, explains historian Luciano Revoredo, adding, “the pisco, as we have mentioned, is a denomination of Peruvian origin. No one else can use this name, only those territories around the Pisco area”.

“Abundant tinajas (clay pots for fermentation), with bullet holes, are a testimony to the barbarisms lived during the war with Chile. Among the geopolitical objectives of Chile was to end the wine and pisco industry in Peru to aid the start their own, and to this end their armies destroyed machinery and shot at fermentation jars”, explains historian Luciano Revoredo, adding, “the pisco, as we have mentioned, is a denomination of Peruvian origin. No one else can use this name, only those territories around the Pisco area”.

Fortunately, Caravelí did not suffer heavy damage in the war. Its industry survived and the Chileans did not pillage and burn the town down, nor massacre its population, as happened elsewhere.

El Cholo Berrocal

The day we arrived, the caravelians were beaming with pride for the official presentation of The Comendador pisco, winner in the competition held days before in Lima. The men wore the finest hats and the women also dressed elegantly. The Peruvian flag was being raised high into the ever-blue sky of Caravelí and a band played the national anthem.

The band also played the work of the great Cholo Barrocal, the famous composer of musica criolla born in Caravelí in 1937 and dying prematurely in Lima in 1983. They did a great job of playing Payaso, as well as No Me Beses and Adiós a la Patria, all hits of Isidoro Barrocal Coronado – his real name.

The band also played the work of the great Cholo Barrocal, the famous composer of musica criolla born in Caravelí in 1937 and dying prematurely in Lima in 1983. They did a great job of playing Payaso, as well as No Me Beses and Adiós a la Patria, all hits of Isidoro Barrocal Coronado – his real name.

We made a point to look all over town for a photo of the great musician, who was blind from the age of eleven and for that reason formed a intimate relationship with his guitar. But we never did find any evidence of his being born and raise here, this idol of idols in the north of Peru as well as Ecuador and Colombia.

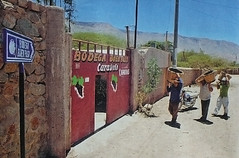

Bodegas

Before going to lunch at the bodega Chirisco, we were told by locals to cover our heads. Everyone wears hats around here due to the fierce burning sun that shines day after day. “It’s been years since it last rained, God has punished us”, said local woman Liliana Montoya, believing more in divine design than climate change. “And when it does rain, the sun comes out twice as strong”.

Before going to lunch at the bodega Chirisco, we were told by locals to cover our heads. Everyone wears hats around here due to the fierce burning sun that shines day after day. “It’s been years since it last rained, God has punished us”, said local woman Liliana Montoya, believing more in divine design than climate change. “And when it does rain, the sun comes out twice as strong”.

In all the bodegas we see huge tinajas, large clay jars used for hundreds of years to produce pisco. The jars are distributed in dark caves, some half-buried with dates like 1612 carved into them, with stylised crosses and a cap of volcanic rock to seal them. Their value is immeasurable, they don’t make these any more.

The owner of Chirisco is Marco Antonio Franco, who has 22 of these jars, where the grapes ferment from between 14 and 20 days. It is he who produces the black creole grape from which the champion pisco El Comendador is made.

Pisco route

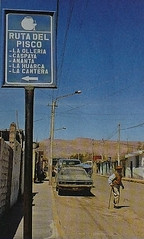

The next day we visited other bodegas of Caravelí, those belonging to the Pisco and Wines Producers Association, otherwise known as the ruta del pisco – the pisco route. It posses incredible scenery and great historic and natural value, in addition to the incredible pisco. The further you travel, towards the edge of the department of Ayacucho and the peak of Sara Sara that sits in our way, we find the Parinacochas lagoon with its flamencos and the Galeras pampa and its vicuñas.

The next day we visited other bodegas of Caravelí, those belonging to the Pisco and Wines Producers Association, otherwise known as the ruta del pisco – the pisco route. It posses incredible scenery and great historic and natural value, in addition to the incredible pisco. The further you travel, towards the edge of the department of Ayacucho and the peak of Sara Sara that sits in our way, we find the Parinacochas lagoon with its flamencos and the Galeras pampa and its vicuñas.

Mario Casas Berdejo, a local intent on showing Peru and the world the riches of Caravelí tells us; “Sometimes some European tourists pass through here. They camp in the higher parts, close to the guanacos and the condors… an incredible area, with forests of queñuales. But above all, the important herds of guanacos, perhaps one of the most important in the country. The problem is that there are hunters, that’s why we are asking that Alto Caravelí is declared a national reserve.

We visited the bodegas of Colca, Buen Paso, La Ollería and finally La Huarca, which has the oldest plants and is very pleasantly located. You really feel like you are out in the country.

We do see a strange structure in the distance though. Mario explains that this is a gold mine, but one Caravelí sees no benefit from due to poor distribution of the revenue. Worse still is that the company that runs it feels little in the way of social responsibility.

We do see a strange structure in the distance though. Mario explains that this is a gold mine, but one Caravelí sees no benefit from due to poor distribution of the revenue. Worse still is that the company that runs it feels little in the way of social responsibility.

We stop for a moment to see the ancient petroglyphs of Ananta, while below us we see the valley of Caravelí, a vibrant fertile green colour, looking as if it is teasing the bleak desert that surrounds it. Mario says the volcanic soil found in his land, like the land of Italy, allows for the cultivation of the perfect grape. He stood there for a while, admiring this view as if it was his first time seeing it.

Now that the sun’s heat was waning, it was time to go home. In Caravelí, life is not measured in hours but in centigrades.

Tags: alvaro rocha, arequipa, bodegas, caraveli, el comendador, pisco, sara sara, war of the pacific, wine