Leguías Lima of the early 1900s

It’s often only by the strong will and determination of a dictator that huge changes can be made to the infrastructure of a city and that public works of an otherwise overwhelming scale can be undertaken and completed in a very short time. That’s what happened to Lima when Leguía seized control, determined to reform the country and the city and return it to its former colonial glory.

Augusto B. Leguía

Born in 1863, he grew up as part of Peru’s super rich oligarchy. He went to school abroad, served as an officer in the Peruvian army in his late teens and left Peru for the United States to become and an executive with the New York Life Insurance Company after completing his studies.

Born in 1863, he grew up as part of Peru’s super rich oligarchy. He went to school abroad, served as an officer in the Peruvian army in his late teens and left Peru for the United States to become and an executive with the New York Life Insurance Company after completing his studies.

Returning to Peru in 1903, wealthier than ever, he was determined to somehow apply the US industrial and capitalist model to Peru. He entered politics and became Finance Minister in the government of the Civilista party alongside José Pardo who went on to become president while Leguía became Prime Minister. In 1907 he resigned to run for the presidency himself and was elected in 1908. As president he immediately began implementing economic reforms.

This was a rocky time that involved an attempted coup and Leguía being kidnapped. There was also a risk of war with all five of Peru’s neighbours over boundary disputes, two of these being resolved by Leguía. He managed to serve out his term and left office in 1912. But that isn’t even the beginning of the story.

After a few years of political turmoil another coup and another election, Pardo was President again. No longer involved with the Civilista party and not even on the best of terms with them, he ran for president once more in 1919 to succeed, for the second time, President José Pardo.

He had every expectation of winning, but feared that the Civilista controlled congress would never recognise his victory. With this in mind, he decided to instead use his funds and influence to launch a military coup. His forces captured the government and he was declared President of Peru after dissolving congress.

Leguía on the cover of Time

Ripping up the old constitution, he introduced a new more liberal one that favoured his ideas and allowed for unlimited re-elections.

Fearing revolts and coups, his suppressed all opposition and exiled his detractors. He was now free to exercise his will.

Making Lima Glorious Again

As part of his plans for a renewed and industrialised Peru was a new capital to rival the colonial city of centuries past. Once the capital of the entire Spanish empire, Lima was the wealthiest and most opulent city in the western hemisphere. It’s checkerboard of streets lined with hand-crafted wooden balconies were the talk of the empire.

It was that feeling of grandeur that Leguía wanted to restore to the capital. It wasn’t the 1500s any more, grandeur and civic opulence were no longer Spanish style wooden balconies, but French and northern European style architecture.

Leguías Lima, which isn’t entirely his work but heavily influenced by him, remained Lima’s new centrepiece until the mid-70s and the slow deterioration of the city. Leguía created a new Lima that again became known around the world, a city that enjoyed a second heyday.

Famous visitors over the years included Ernest Hemingway, Richard Nixon, William Faulker, Edward VIII, Greta Garbo, Charles de Gaulle, Nelson Rockefeller, Fulgencio Batista, Ava Gardner, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards. The Rolling Stones even wrote a song here called “Let it Bleed”. After returning from the moon, Neil and Buzz Armstrong were paraded through the streets of Lima to cheering crowds.

Let’s take a trip to the past…

It may surprise you to discover that the now famous and obligatory tourist stop of the Plaza San Martín didn’t used to exist. In 1914 when the above photo was taken it was home to a railway/tramway station which itself had replaced the colonial building of the San Juan de Dios hospital.

Under Leguía’s direction, this was torn down to make way for the glorious gleaming white plaza we see today, complete with marble finishings and the centrepiece statue of San Martín the independence hero.

Above we see the construction of the Plaza, below too.

The end result was stunning…

…and stayed that way until the 70s – right through Lima’s hip 60s.

As millions of rural peasants poured into the city decades later, fleeing harsh lives of exploitation and then leftist extremists the Sendero Luminoso, Leguía’s Lima faced socio-economic collapse. Filled with garbage and street sellers through the 1980s, it has only fairly recently been restored. The money however has long since left.

Before and After the Plaza San Martín…

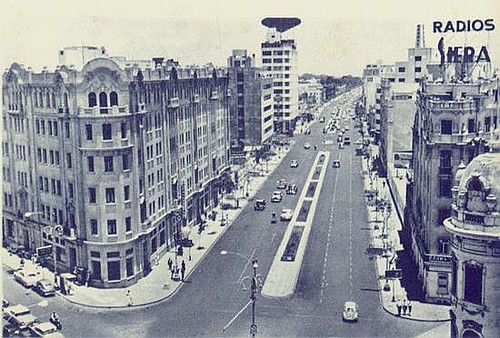

In building the Plaza San Martín, Leguía also oversaw the building of and new city avenue, La Colmena. This was Lima’s version of New York’s Fifth Avenue or London’s Regent Street as was home to some of the cities finest businesses.

Let’s look down La Colmena from the Plaza during Leguía’s time…

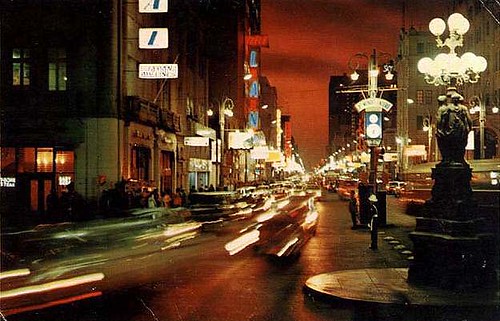

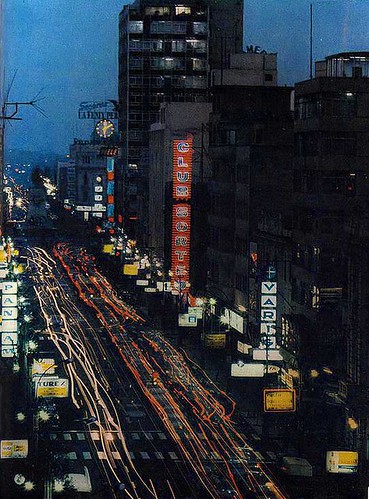

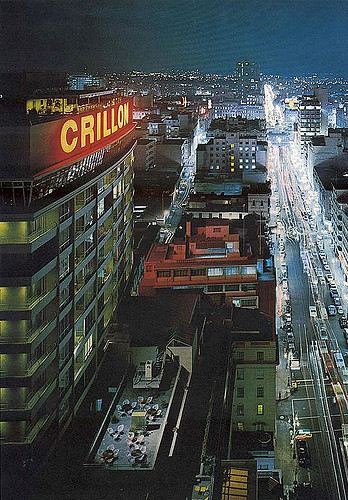

As the years progressed, La Colmena was all lit up…

Nearby Av. Wilson looked like this…

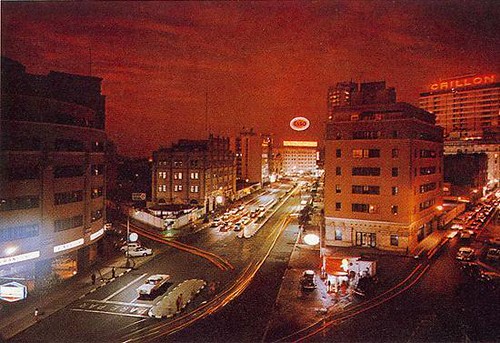

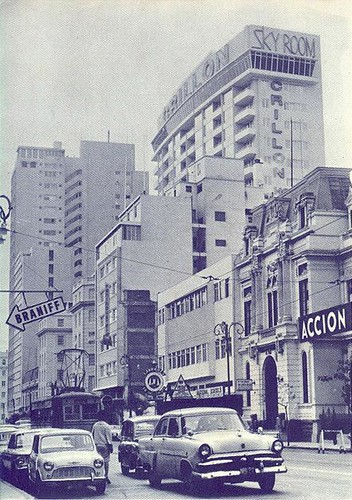

Before Lima’s “fall”, other than the Hotel Bolivar on the Plaza San Martín, there was the Hotel Crillón on Av. Colmena.

A simple looking hotel at first…

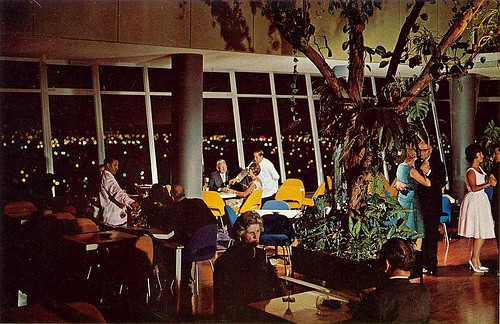

…with the addition of the Sky Room tower in later years it was a major centre point for the capital.

As the 70s came, La Colmena lost a little of it’s appeal as fancy businesses moved out and less prestigious businesses moved in.

As the 80s came, many more businesses moved out and drug addicts, criminals and street sellers moved in as Lima and Peru hit a free fall.

Today you’ll find the Hotel Crillón as abandoned as it has been for decades, the rich as famous at it’s gates replaced by street children and beggars.

A visible police presence during the daytime keeps the area much safer that it once was, and the street is now known for its shops selling musical instruments. As poverty decreases and investment increases, perhaps La Colmena will eventually retain it’s former glory.

La Colmena (now called Piérola) right next to Plaza San Martín, with Hotel Bolivar on the left.

Another of Leguía’s great creations was the Avenida Leguía, today known as Av. Arequipa. This impressive avenue runs from the area of central Lima referred to by this article as “Leguía’s Lima” all away to the tiny seaside town of Miraflores.

Along this wide suburban street was for the most part nothing. Here and there it cut through a hacienda and it’s country house with houses for workers, Lince in particular, but in no time the rich began to build mansions, slowly moving out of colonial-era Barrios Altos and starting the trend of migration towards the south and to the beaches. The new avenue meant living in the once distant beach towns was no problem at all.

At the start of this new avenue was a great monument, the Arco Morisco. This arch in Moorish style was built in 1924 but torn down just years later in 1939 to supposedly make way for traffic. This is just one example of Lima mayors regular destruction of monuments.

A replica was completed in 2001 in the Parque de La Amistad in Surco, and the King and Queen of Spain Juan Carlos I and Sofia attended its inauguration.

Lima’s Plaza Dos De Mayo was built in the 1800s on the edge of colonial Lima and what was becoming the upper-middle class district of Breña. But the blue buildings didn’t come to decorate it until Leguía’s time, when wealthy businessman Rafael Larco Herrera donated them to the city.

Here they are not long after completion…

This was Plaza Grau around the same period, before the Centro Civico, before the Sheraton Hotel and before the Palacio de Justicia.

Located at the edge of the city and the beginning of a new suburbia set to sprawl all the way to Miraflores, here were located large parks, of which the recently restored Parque de la Exposición and Circuito Mágico de Agua have retained a sense of former glory.

Back to Dos de Mayo, we move down Av. Alfonso Ugarte to find something a little unusual.

Super rich Larco Herrera built this place to hold his private collection of pre-Colombian artefacts. Leguía thought it would make a great public museum and so bought it along with the entire collection.

So decades later the Larco Herrera Museum eventually ended up in the hands of state entity the INC. The ceramic items made their way to other museums such as the Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú in Pueblo Libre and the museum became instead the Museum of Peruvian Culture. The Larco family would later build another museum of their own, also in Pueblo Libre, buying collections from tomb raiders across the country.

Above you see Paseo Colón, in the second picture all the way into Plaza Bolognesi, surrounded by identical buildings just as with Plaza Dos de Mayo about 5 minutes away.

Today Plaza Bolognesi and Paseo Colón are not quite so pretty and in some places, falling apart.

The changes to Lima during what was the time of Leguía were numerous. Add to the above the Palacio de Justicia in Plaza Grau, the current Congress building, a great children’s hospital, and the Hospital Arzobispo Loayza to name a few, all built with a sense of grandeur befitting a great city.

President Leguía initiated similar grand works across the country as well as implemented a number of reforms… such as founding the Central Reserve Bank of Peru.

After 11 years in power, and numerous changes to the constitution allowing this strong willed dictator to do as he pleased, social unrest finally caught up with him. On the 22 of August 1930, a coup was launched, starting in Arequipa by military commander Sánchez Cerro.

Ageing Leguía was also quite sick, and gave in without much of a fight, handing the reigns of power over to the new dictator somewhat cordially. These was little appeasement for the new government who instead of letting the old man die peacefully in his home, sent him to a squalid cell in the prison on the San Lorenzo island. Here, because of the terrible conditions, he died of pneumonia less than two years later, aged 69 and completely penniless.

Tags: 1900s, arco morisco, augusto b. leguia, avendia alfonso ugarte, avenida arequipa, avenida garcilaso de la vega, breña, central bank, dictatorship, hospital arzobispo loayza, hospital de niños, hotel bolivar, hotel crillon, jose pardo y barreda, la colmena, larco herrera, lima, palacio de justicia, paseo colon, photography, plaza bolognesi, plaza dos de mayo, plaza grau, plaza san martin, pueblo libre, teatro colon